All products are independently selected by our editors. If you purchase something, we may earn a commission.

The first thing Lindsey Taylor wants you to know about her dazzling new book, Art in Flower (Monacelli Press, 2023), is that it is not meant to teach you how to arrange flowers. ‘I’m not interested in explaining the mechanics of making grand arrangements, but rather the opposite. The point is to be spontaneous, to stop overthinking it. To turn the act of putting flowers in a vessel a daily practice, not an undertaking reserved for special occasions,’ she says.

The Toronto-born Taylor has been at it since she was a child, tasked with ‘doing the flowers’ for her parents’ dinner parties. A passion blossomed into an editorial career, launched at an era-defining Martha Stewart Living magazine and winding its way through the cult favourite Domino quarterly, the estimable T Magazine and ultimately The Wall Street Journal. Through it all, Taylor grew her distinctive flower personality. Her column for the Journal, Flower School, in which she interpreted works of art into arrangements, allowed the garden designer to do some of the things she loves most: look at art, gather flowers, create arrangements, discover new ceramicists, collaborate with photographers and write.

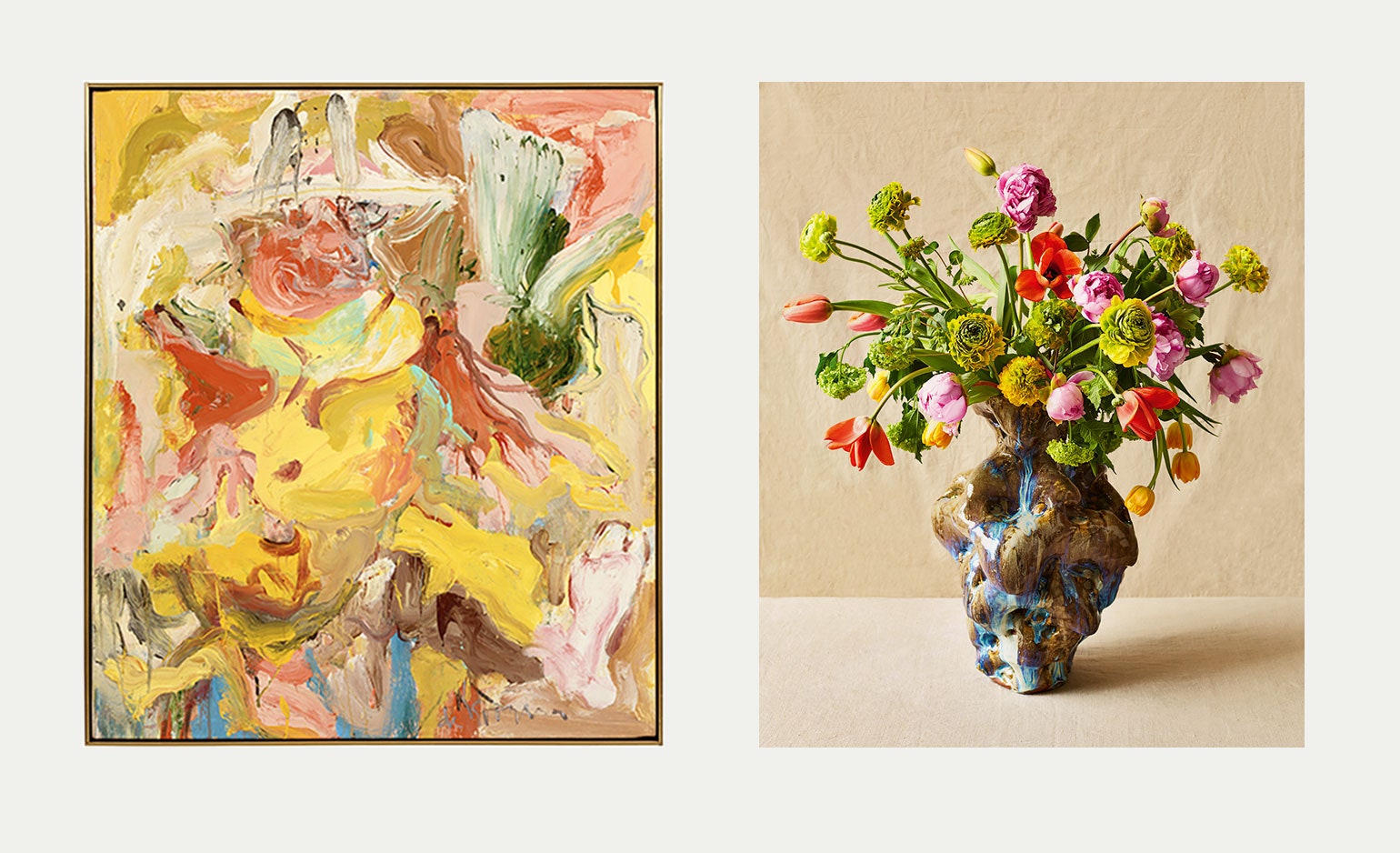

Paging through the beautifully designed Art in Flower, it is clear that Taylor takes observation seriously and interpretation playfully. ‘The closer you look, the longer you look, the more patient you are, the more you see. How to interpret what you see is up to you,’ she says. Flip back and forth between a chosen painting and Taylor’s floral interpretation of it, and you might imagine she spent hours and excessive resources to achieve it. But this is a woman who worships at the altar of British society florist Constance Spry, who in the 1930s was famous for shocking the upper classes and royalty by using vegetables, leaves, berries and ornamental grasses in her clients’ displays. She declared roadside weeds just as beautiful as roses.

‘I am from the “use what you have” school. The goal, really, is to connect more deeply, more intentionally, with nature and with art,’ she says. Organised by season and featuring as idiosyncratic a group of artists — from Lois Dodd, Alice Neel and Kerry James Marshall to Whistler, Renoir and Giovanni Bellini — as the inspired arrangements and vessels themselves, Art in Flower finds Taylor taking to heart the advice of her hero, Spry: ‘Do what you please, follow your own star; be original if you want to be and don’t if you don’t want to be.’

For a late-spring arrangement, Taylor looked to Julie Mehretu’s work Retopistics: A Renegade Excavation (2001). Against its monumental off-white background (the acrylic-and-ink painting is five by two-and-a-half metres), a bright explosion of lines, drips, ribbons and geometric shapes swirls over architectural drawings. Taylor chose a matt-black vessel, secured a floral frog inside to hold up each stem and used alliums, carnations, globe thistles, hyacinths, leucojum, muscari, ranunculus, star of bethlehem and tulips to perform versions of the colourful gestures in Mehretu’s work.

Summer fun was on Taylor’s mind when she chose Salman Toor’s Four Friends (2019), depicting young men dancing and socialising. The contagious energy and free use of greens — and the swaying limbs, like flowers in a breeze – captivated her. Taylor saw two chestnut-brown vessels in the dark furniture, a single black one in the cell phone, and then depicted all those greens through the vibrant stem of a single tuberose, eucalyptus foliage and queen anne’s lace bending and cascading. Soft pink ranunculus and delphiniums call out the colourful clothing.

It’s never easy to get close to the Mona Lisa, physically or emotionally. So Taylor decided to try by attempting to transform the intrigue and beauty of Leonardo’s masterpiece (1503–6) with autumn flowers. A brownware jug picks up on the richness of the sitter’s dress, while ninebark’s green-umber foliage stands in for the painting’s landscape. Astilbe mimics her skin tone, while the long seed heads of andromeda recall her fingers. A few chocolate cosmos evoke her clothes, and kangaroo paws’ deep-red flowers and the orange balls of gomphrena add colour and texture. A few stems of delphinium conjure the background water and sky.

The winter garden offers few vibrant tones for cutting, so Taylor sought to make a mood-elevating arrangement. Having seen a show of Picasso’s sculptures, at around the same time she came across ceramicist Frances Palmer’s white earthenware vessel, which reminded Taylor of the face in Picasso’s The Red Armchair (1931). From the flower market and a local deli, she sourced a bold mix of purple anemones, yellow roses, red parrot tulips, orange kumquat cuttings with green leaves, deep-plum ninebark and nandina foliage, then colour-blocked them and added a final flourish – another of Palmer’s pieces in porcelain sang de boeuf glaze, with a single tulip draped over the rim. Winter listlessness banished.