Arthur Lasenby Liberty’s eponymous establishment was not only the ‘chosen resort of the artistic shopper’ in London, as avid customer Oscar Wilde put it. In Italy, a new architectural stile floreale blossomed in the late 19th century – in tandem with the fashionable eclecticism of the Regent Street emporium. Marrying stylistic elements of Baroque, Art Nouveau and Art Deco, the style was christened ‘Liberty’ after the department store that had become renowned for its Oriental objet d’arte, ornaments and textiles. Larger Italian cities, such as Milan, Turin and Palermo, in particular, adopted the Liberty aesthetic in a bid to dissociate their urban identity from that of Rome, and this dovetailed with a change in the social fabric of Italy. The Risorgimento had toppled the absolute monarchy, and the bourgeoisie, newly moneyed from rapid industrialisation, had overtaken the nobility in terms of setting aesthetic trends in design, art collection and architecture.

Casa Crespi in Milan reflects this cultural milieu. Designed for the entrepreneur Fausto Crespi by Erminio Alberti – an engineer by trade – in the 1920s, it was constructed on the site of the owner’s factory, which produced metal furnishings for offices, ships and hospitals. Perhaps as a consequence of the short-lived nature of the Liberty style (after World War I, Roman Neoclassical Rationalism was championed by Benito Mussolini’s fascist dictatorship, and more ‘frivolous’ architectural styles were abandoned in favour of government patronage), little is recorded about Alberti’s work as an architect, though he designed both private and public buildings in Milan in the early 20th century. As such, Casa Crespi remains a rare example of his idiom, and stands as totem of the collaboration between an architect and man of industry.

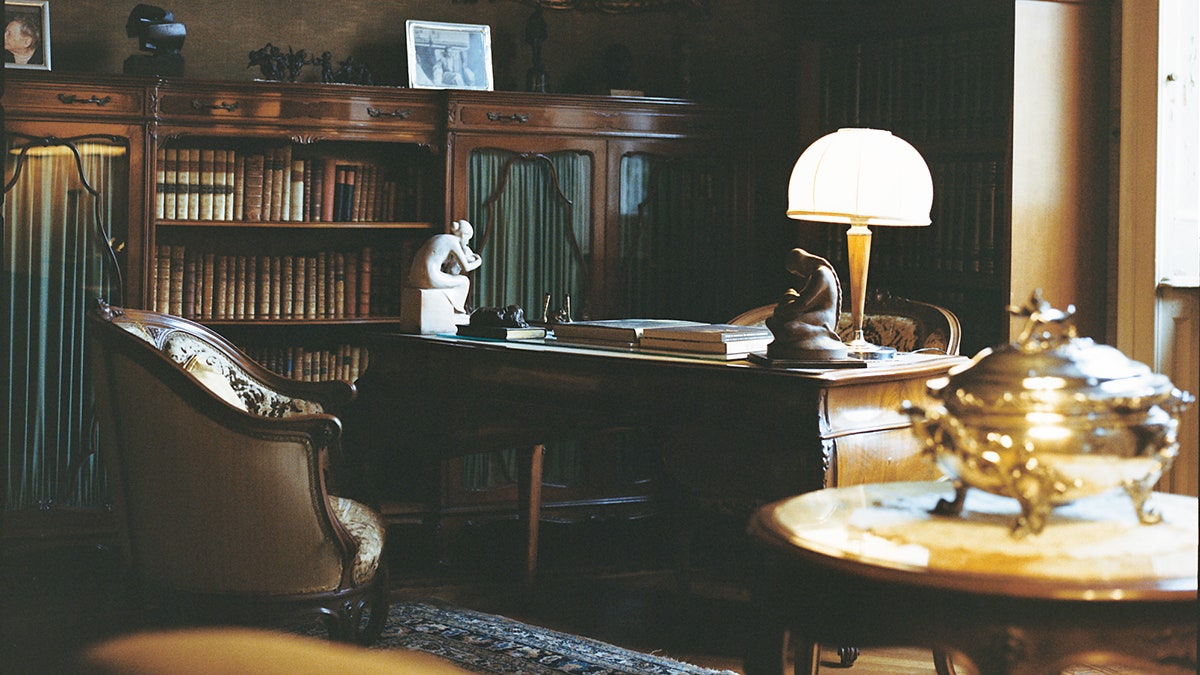

Fausto Crespi, his wife and five children took up residence at Casa Crespi in 1931. By that point, Rationalism had taken over as the primary architectural style and ideological outlook, but the interiors of Casa Crespi reflect a more bourgeois sensibility, tempered by the sober taste of the industrialist. Many of the furnishings are metal – a modern conceit no doubt influenced by Crespi’s business – but the general composition and decorative style is a reflection of the interests of Milanese bourgeoisie at the time: cultural and academic pursuits, working life and refined luxury.

The well-known polymath Alberto Crespi grew up in the house, and later made his mark on it. A graduate of the Milan Conservatory, the alma mater of Giacomo Puccini and Gian Carlo Menotti, Alberto was passionate performer of German Baroque organ music, though he later switched to law and rose to prominence as a jurist in the field of white-collar crime. Despite devoting much of his career to the latter, he never lost his passion for music and had one of the downstairs bathrooms at Casa Crespi demolished and refitted with a 1,500-pipe organ, on which he’d no doubt have played Bach (a childhood favourite). This is one of the few changes made to Casa Crespi in its 90-year history, though Alberto’s fervour for collecting art has since added to the rooms an eclectic mix of styles (much like Liberty, indeed, at large) – 15th-century Lombardi sculptures and 17th-century Roman paintings; rare books and antiques of all forms.

Like his father, Alberto partnered with an architect to design a space for his treasures. In collaboration with Giovanni Quadrio Curzio, Fausto’s successor designed a wing in the Museo Diocesano to house the Fondi Oro Collection, 41 gold-leaf artworks made between the 14th and 15th centuries. It was in this spirit that Alberto and his brother, Gianpaolo, donated Casa Crespi to Fondo Ambiente Italiano, Italy’s National Trust, in 2013. Due to open to the public in 2026, the house is a triumph of preservation. Hardly altered in almost a century, it remains an exemplar of the style and social outlook at the time, mixing utilitarian modcons and Art Deco decorative elements with antique furniture, art and heirlooms. It was once written of Liberty that it was ‘a dazzling dream […] in all its infinite variety’, and much the same can be said of Casa Crespi.